Ez az angol fordítás. Az erdeti magyar verzió itt olvasható.

Foreword

One of the funniest scenes from the eternal classic “Life of Brian” is when a group of enraged Jews are scheming about how they’re going to kidnap Pilate’s wife to give force to their independence demands. The community leader, after listing how the damn Romans have already exploited their fathers (and their fathers’ fathers, and even their fathers’ fathers’ fathers), poses that provocative question - which has since become a catchphrase - “What have the Romans ever given us?”

Anyone who has seen it surely remembers that instead of the expected rage-filled answers like “Absolutely nothing, the bloody bastards!”, unexpected responses start pouring from the group of plotters: “aqueducts”, “sanitation”, “roads”, “irrigation”, “medicine”, “education”, “wine”, “public safety” and in the end it turns out that the Romans “brought peace” too. I honestly envy anyone who hasn’t seen it yet and can watch it for the first time, here’s the link to the scene.

It’s been almost 9 years since I wrote my previous “Emigrant/Immigrant” post. I wrote that on the fifth anniversary of our emigration to London and it was a reflection on all the things that experience has taught me. Well, after 14 years in self-inflicted exile, we still don’t live in Hungary, but we have doubled in size as a family and moved to another country. However, I’m slowly approaching forty and so I’m increasingly occupied with our family’s history, so it recently occurred to me: how would I answer, if I found myself in the above mentioned scene - but with a twist - where we’d replace Rome with Hungary. The question therefore is: “What have the Hungarians given us?”

I think every Hungarian will have an answer to this strange question, one that builds on their own origins and family history. Also, it goes without saying, replacing Hungary with any other country results in an equally interesting thought exercise. Regardless of what the response sounds like to this strange question, I would honestly encourage everyone to do the intellectual and spiritual work necessary to answer the question, because it can be cathartic. It was for me.

Here is my, or rather our family’s answer, which for the sake of comprehensibility, I compiled from the stories of my four grandparents’ immediate families, using only first names - so as not to make the exact identity of the persons completely public.

Paternal Grandfather’s Line

My 3rd great-grandfather, Rudolf, was the director of the first Slovak gymnasium and an protestant chaplain during the monarchy era, in what is now Slovakia - in a town called Nagyrőce. The fact that a town had the opportunity to teach its students in Slovak was such a big deal at the time that a memorial plaque still preserves my 3rd great-grandfather’s name in the museum of Nagyrőce to this day. But to understand why, I need to provide a bit of background.

My 3rd great-grandfather, Rudolf, was the director of the first Slovak gymnasium and an protestant chaplain during the monarchy era, in what is now Slovakia - in a town called Nagyrőce. The fact that a town had the opportunity to teach its students in Slovak was such a big deal at the time that a memorial plaque still preserves my 3rd great-grandfather’s name in the museum of Nagyrőce to this day. But to understand why, I need to provide a bit of background.

The Compromise of 1867 turned the Austro-Hungarian Empire into a real union between the Austrian Empire in the western and northern half and the Kingdom of Hungary in the eastern half. During this period, the Hungarian government started to force the Hungarian language onto the non-Hungarian peoples of her territories in an ever more forceful way. This was done to speed up the assimilation of the dozen or so non-Hungarian ethnic groups who all lived in the Eastern part of the wildly multi-cultural and mult-religious Austro-Hungarian Empire. In line with these chauvinistic aspirations, in the 1860s and `70s, the Hungarians closed almost all Slovak-language gymnasiums, since they considered these the antechamber for training the Slovak elite and thus the kindling for the Slovak national movement. In 1874, the gymnasium led by my 3rd great-grandfather was also closed. Nonetheless, Rudolf stayed in the town and died 24 years later.

An interesting side note: Gyula Rochlitz was Rudolf’s contemporary, who was also born and raised in Nagyrőce. He was an architect from a Saxon family, educated at Vienna University, who emigrated to Western Europe and then returned to Budapest, where he designed the main building of the Eastern Railway Station in Budapest. His story shows not only the incredible ethnic and cultural diversity of the monarchy, but also the opportunities within it. End of side note.

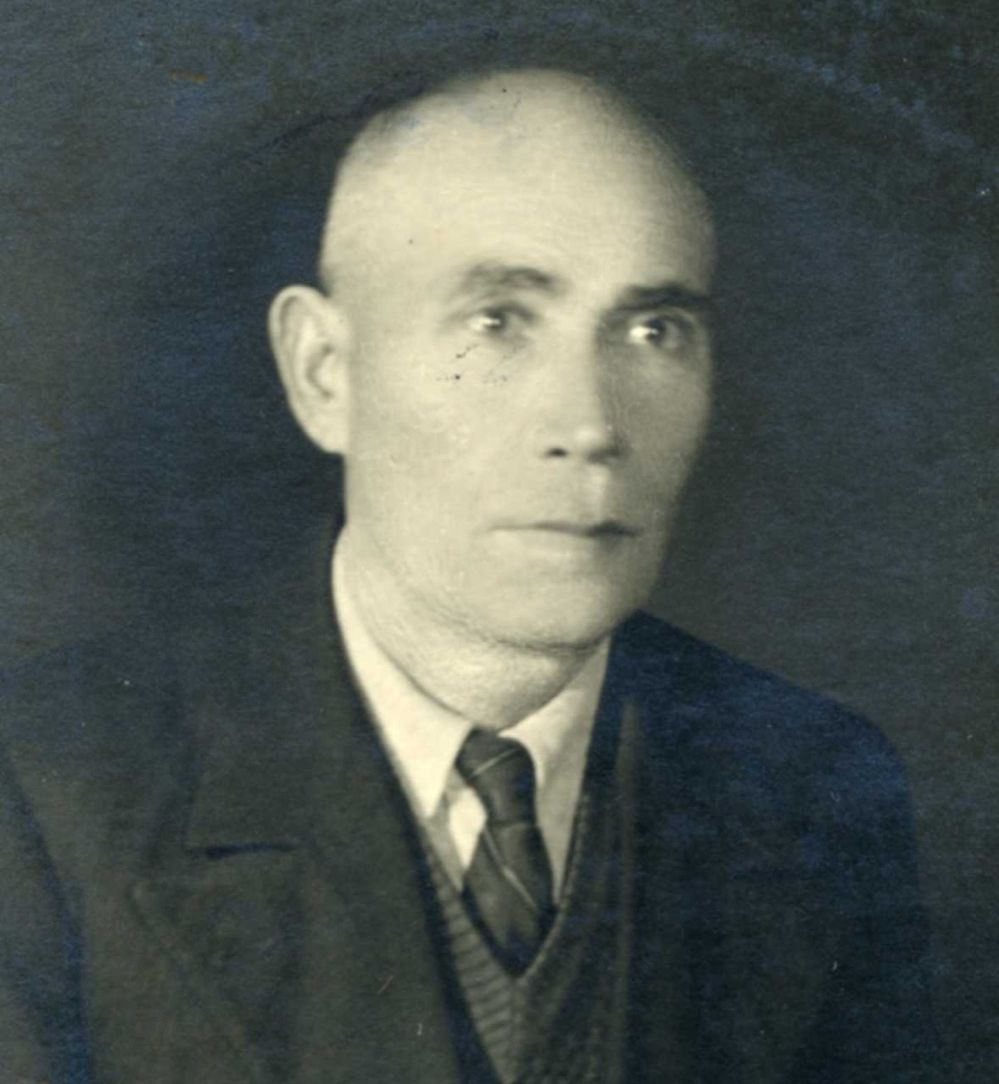

My paternal great-great-grandfather, Gyula, already lived mostly in Nagybánya (in today’s Romania) and died there too. He worked as chief mining accountant. They had a house in the old-town, in Castle Street, where his two two sons and three daughters were born. His younger son, Viktor Lajos, is my great-grandfather, who as a certified engineer, after positions in a series of towns, finally settled in Pécs (city in South Hungary) and died there in his vineyard in the Mecsek hills. By this time the family had clearly become Hungarian - both in language, and presumably culturally.

My paternal great-great-grandfather, Gyula, already lived mostly in Nagybánya (in today’s Romania) and died there too. He worked as chief mining accountant. They had a house in the old-town, in Castle Street, where his two two sons and three daughters were born. His younger son, Viktor Lajos, is my great-grandfather, who as a certified engineer, after positions in a series of towns, finally settled in Pécs (city in South Hungary) and died there in his vineyard in the Mecsek hills. By this time the family had clearly become Hungarian - both in language, and presumably culturally.

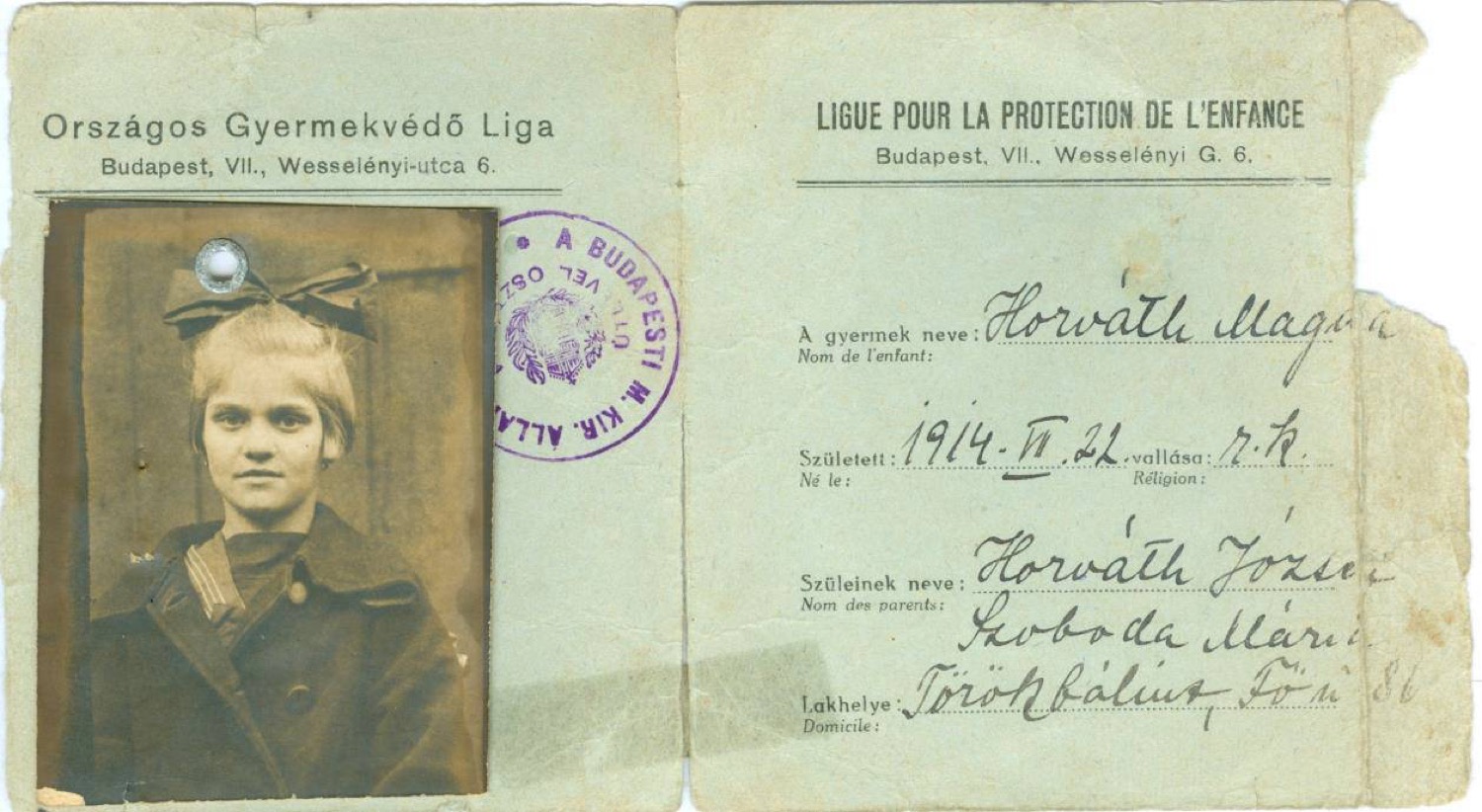

Viktor Lajos’s wife, my great-grandmother was Róza, who was born into a family in Törökbálint - a town close to Budapest. They met when my great-grandad was working in the capital within the framework of the mandatory military demobilization after World War I, as a state employee. Róza had a total of six full siblings and four half-siblings. Her father, that is, my other great-great-grandfather, was János, who came from Czechoslovakia originally and worked as a butcher. According to turn-of-the-century photos, they lived in prosperity, but the family’s story later took sad turns. His first wife, Franciska, died giving birth to their seventh child, and the economic crisis after World War I led to terrible poverty and a series of tragedies. Of János’s 11 children from two wives, only three lived to adulthood, while the rest became victims of tuberculosis.

Viktor Lajos’s wife, my great-grandmother was Róza, who was born into a family in Törökbálint - a town close to Budapest. They met when my great-grandad was working in the capital within the framework of the mandatory military demobilization after World War I, as a state employee. Róza had a total of six full siblings and four half-siblings. Her father, that is, my other great-great-grandfather, was János, who came from Czechoslovakia originally and worked as a butcher. According to turn-of-the-century photos, they lived in prosperity, but the family’s story later took sad turns. His first wife, Franciska, died giving birth to their seventh child, and the economic crisis after World War I led to terrible poverty and a series of tragedies. Of János’s 11 children from two wives, only three lived to adulthood, while the rest became victims of tuberculosis.

Several of his daughter Mária’s children - within the framework of the contemporary Belgian child rescue program - ended up in Belgium to avoid starvation. However, instead of staying just a few short months, they remained forever. The connection with this separated family tree branch - still living in Belgium - was revived by my father’s genetic test, which helped them find us.

Several of his daughter Mária’s children - within the framework of the contemporary Belgian child rescue program - ended up in Belgium to avoid starvation. However, instead of staying just a few short months, they remained forever. The connection with this separated family tree branch - still living in Belgium - was revived by my father’s genetic test, which helped them find us.

As I mentioned, my great-grandfather, Viktor Lajos, lived and worked in several cities until he finally became the director of the Flood Control Association in Pécs, so they settled there. He later bought a plot near Lake Balaton, but offered this to the Balaton Society for vacationing war orphans, in exchange for financing his sons’ university education.

As I mentioned, my great-grandfather, Viktor Lajos, lived and worked in several cities until he finally became the director of the Flood Control Association in Pécs, so they settled there. He later bought a plot near Lake Balaton, but offered this to the Balaton Society for vacationing war orphans, in exchange for financing his sons’ university education.

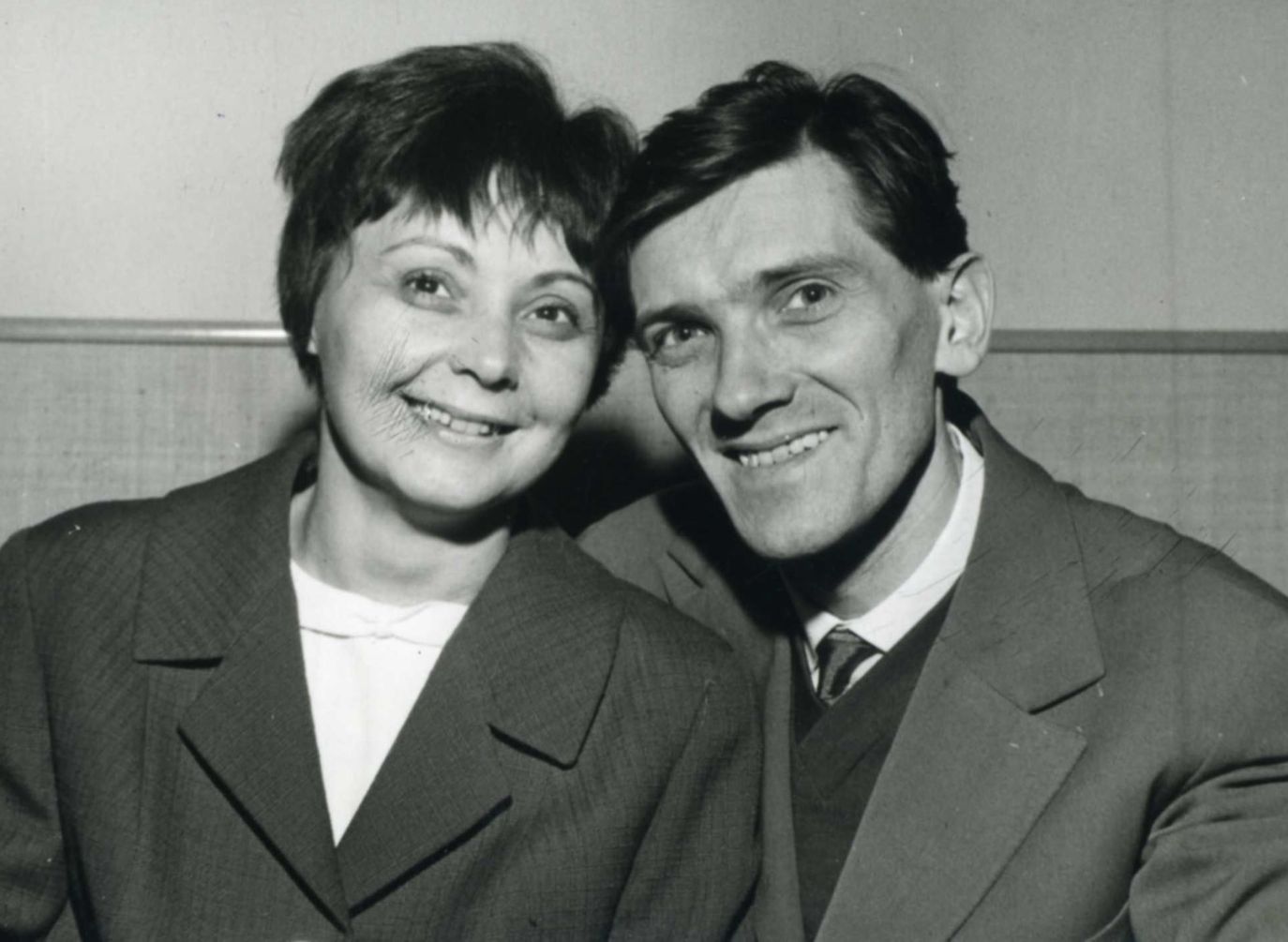

When my grandfather, Viktor (to me, simply Vikó) came to Budapest to study engineering after World War II, he moved in with his uncle Laci, into his apartment overlooking the Southern Railway Station. Uncle Laci studied law and worked as a judge. In the communist Rákosi regime, he constantly feared forced deportation due to his position and middle-class life - not without reason, because this had already happened to several of his friends, as part of the anti-intellectual purge of the communist party. This constant fear and stress drove the poor man all the way to a heart attack which caused his death. His wife committed suicide one day later: she simply put her head in the oven and turned on the gas tap. My grandfather, still a university student living with them, found them, and it was a near miracle he didn’t ring the doorbell and the apartment didn’t explode. Our family graves are in Farkasréti Cemetery today because that’s where Viko found a place for them in the neighbourhood.

When my grandfather, Viktor (to me, simply Vikó) came to Budapest to study engineering after World War II, he moved in with his uncle Laci, into his apartment overlooking the Southern Railway Station. Uncle Laci studied law and worked as a judge. In the communist Rákosi regime, he constantly feared forced deportation due to his position and middle-class life - not without reason, because this had already happened to several of his friends, as part of the anti-intellectual purge of the communist party. This constant fear and stress drove the poor man all the way to a heart attack which caused his death. His wife committed suicide one day later: she simply put her head in the oven and turned on the gas tap. My grandfather, still a university student living with them, found them, and it was a near miracle he didn’t ring the doorbell and the apartment didn’t explode. Our family graves are in Farkasréti Cemetery today because that’s where Viko found a place for them in the neighbourhood.

After his uncle and wife’s death, my grandfather “claimed” part of the apartment from the Council. They granted him the use of the flat due to his demonstrator work at the university. The tiny apartment was later divided by the Council into a three-way shared rental. During the post-war communist times, it was common to house two, three or even more families within the same apartments. Although unthinkable by today’s standards, millions of people lived like this across the Soviet Union, sharing the toilets and bathrooms on a tight schedule with other families. This meant, an entire family had to cram into a single room - or sometimes not even that, just a hallway. My father and his two younger brothers were also born in this apartment and lived here for a while, sharing it with two other families. Moreover, during the Revolution of ‘56 the Russians shot at the house - because there was a rebel machine gun nest on its roof. Later, when the Russians entered the house they threw a grenade into the shelter where my grandfather, grandmother, and my then-infant father were hiding. They owed their lives to the fact that the shelter was protected by a double door, but the Soviet soldier only opened the first one.

Gallery

Summary: my paternal grandfather’s line is a family of Slovak-descent who later Hungarianized. They were protestants who were mainly engineers, lawyers and middle-class intellectuals. Traveling the route of Nagyrőce, Nagybánya, Törökbálint, Debrecen, Pécs, Budapest, they ended up in the Hungarian capital. Uncle Laci’s and his wife’s tragic death is clearly attributable to the communist regime.

Paternal Grandmother’s Line

My 5th great-grandfather, Vencel, was born in Prague in 1735, but died in Pécs, Hungary. We don’t know how or why he moved over, but given their Germanic surname, the family was presumably German-speaking at the time.

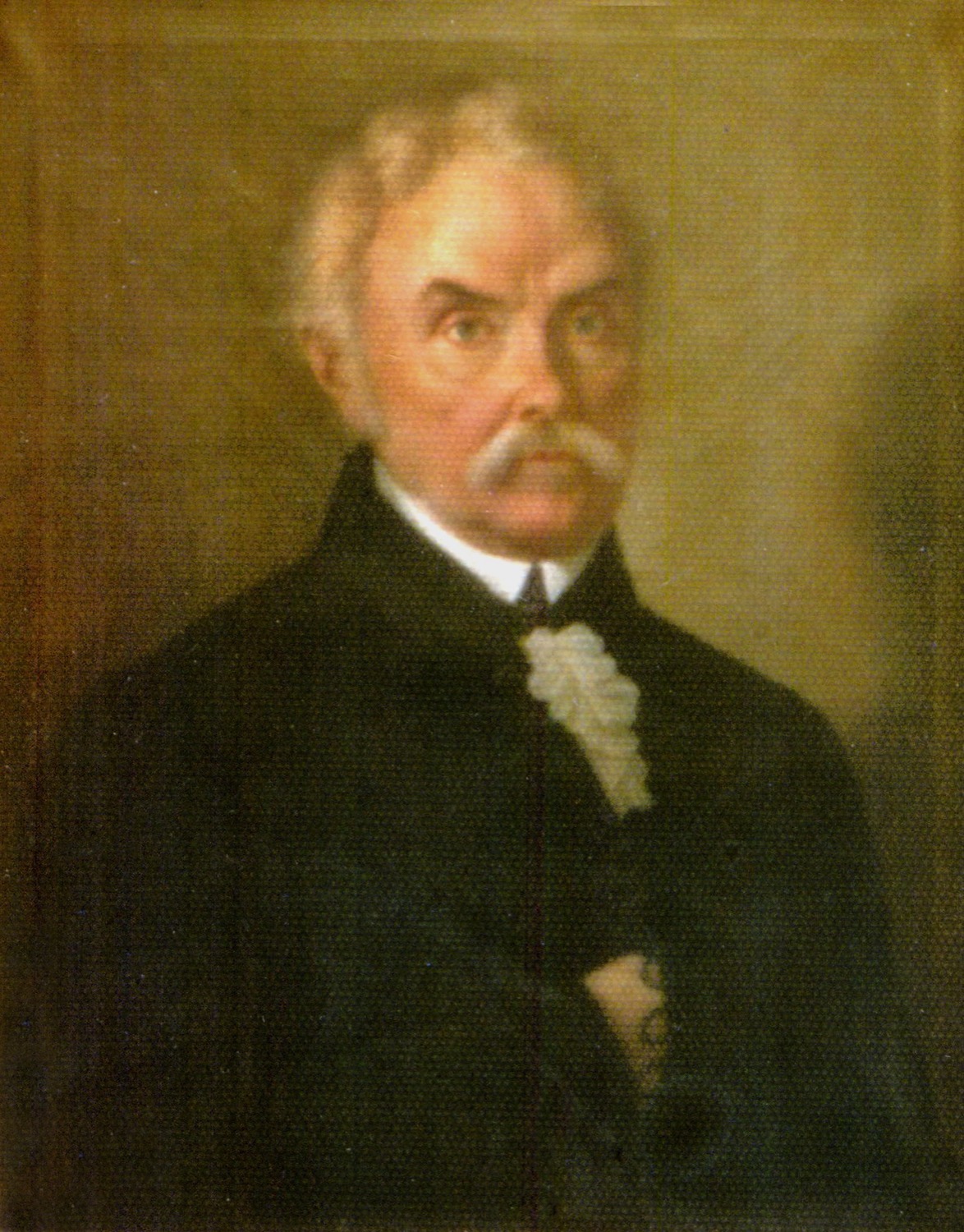

Vencel had five sons, of whom my ancestor, my 4th great-grandfather, József, was the accountant of the Pécs cathedral chapter in the first half of the 19th century. Later, he received a patent of nobility from King Francis I on April 11, 1828, and with that he became a landowner and minor nobleman in Somogybabod. A recreated version of the coat of arms from its contemporary description still exists and is hanging on the wall of my father’s study. The patent of nobility was confiscated by the Communist State Security in July 1950.

Vencel had five sons, of whom my ancestor, my 4th great-grandfather, József, was the accountant of the Pécs cathedral chapter in the first half of the 19th century. Later, he received a patent of nobility from King Francis I on April 11, 1828, and with that he became a landowner and minor nobleman in Somogybabod. A recreated version of the coat of arms from its contemporary description still exists and is hanging on the wall of my father’s study. The patent of nobility was confiscated by the Communist State Security in July 1950.

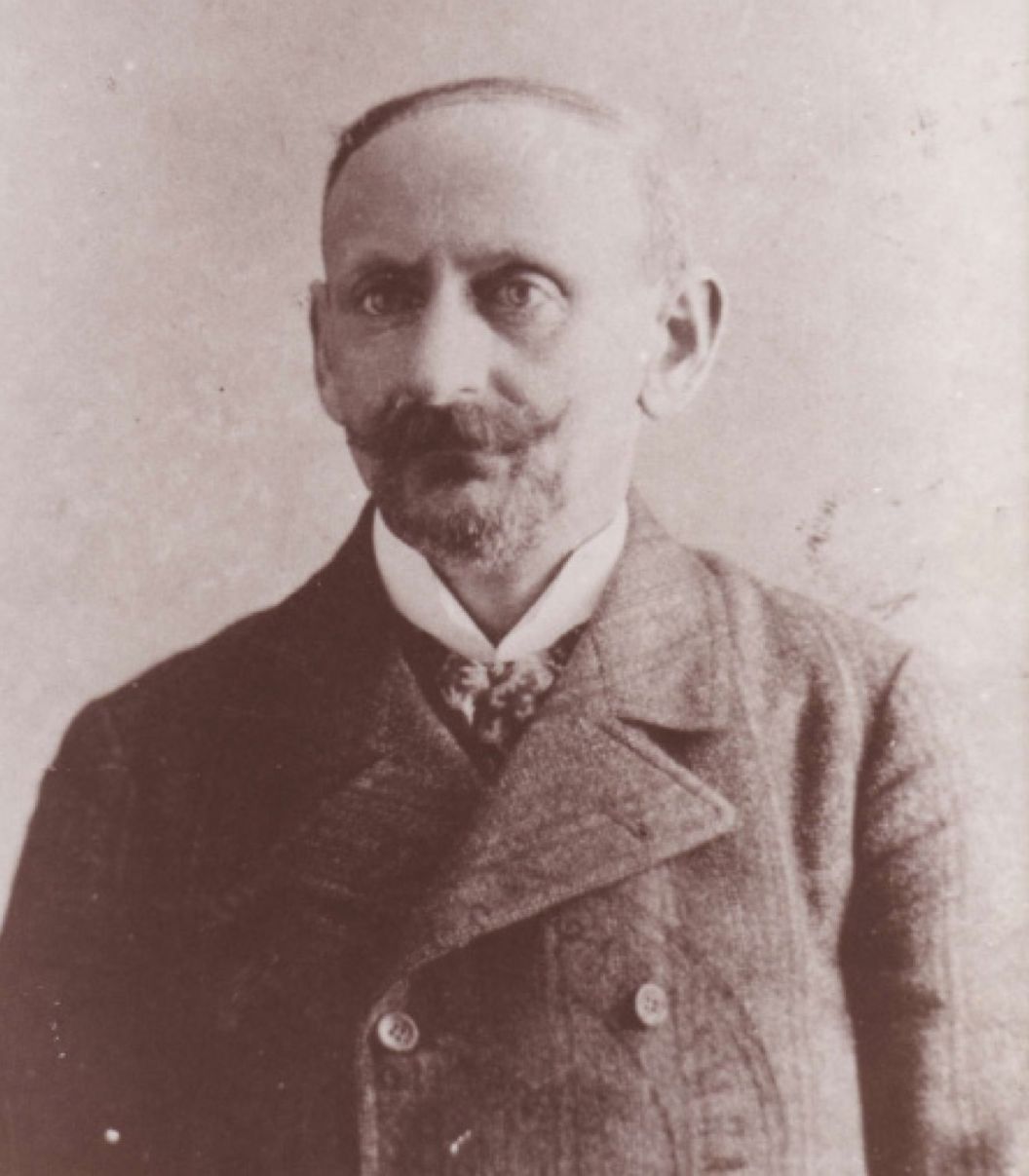

The three generations following József gradually shed their landed gentry lifestyle and became bourgeois, relying on their legal education. My great-grandfather, Kálmán, sold the 900-hectare estate to the Hungarian Academy of Sciences around 1890 and they moved to Pécs. Here they and the following generations all worked in various judicial positions in public administration and lived the characteristic life of middle-class intellectuals.

The three generations following József gradually shed their landed gentry lifestyle and became bourgeois, relying on their legal education. My great-grandfather, Kálmán, sold the 900-hectare estate to the Hungarian Academy of Sciences around 1890 and they moved to Pécs. Here they and the following generations all worked in various judicial positions in public administration and lived the characteristic life of middle-class intellectuals.

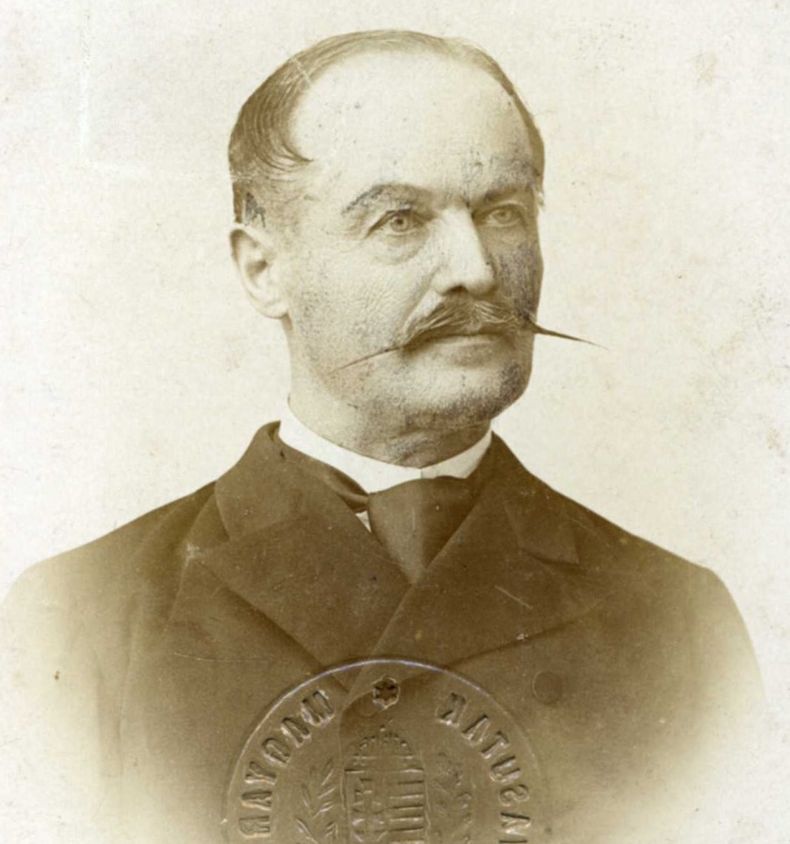

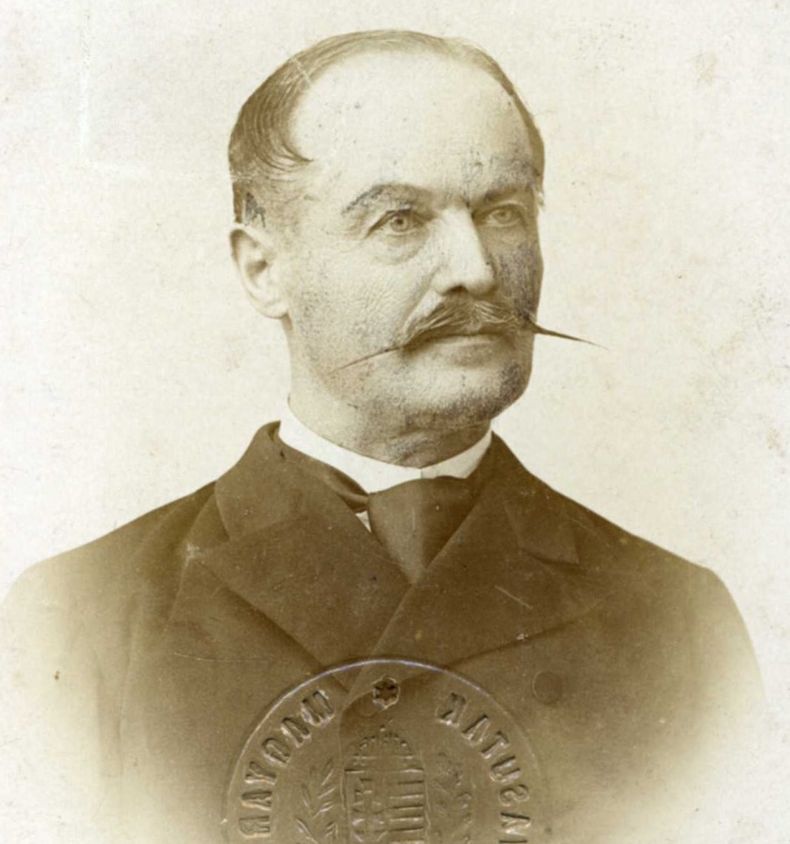

My great-grandfather - who also runs as Uncle Laci in the family history - was born in Pécs, but in addition to his legal education, he also earned a mining engineering diploma from Sopron. Sopron is a city that is now on the border of Austria and Hungary and after World War I, its fate was decided in a now legendary referendum that asked its citizens whether they wanted their city to be part of Austria or Hungary. During this referendum, my great-grandfather and his university companions voted multiple times daily, based on names found in the cemetery, so that Sopron would remain a Hungarian city. As we know, they succeeded.

My great-grandfather - who also runs as Uncle Laci in the family history - was born in Pécs, but in addition to his legal education, he also earned a mining engineering diploma from Sopron. Sopron is a city that is now on the border of Austria and Hungary and after World War I, its fate was decided in a now legendary referendum that asked its citizens whether they wanted their city to be part of Austria or Hungary. During this referendum, my great-grandfather and his university companions voted multiple times daily, based on names found in the cemetery, so that Sopron would remain a Hungarian city. As we know, they succeeded.

After graduating, he worked as a mining engineer where by sheer luck the miners unearthed the remains of a woolly mammoth. My great-grandad led the excavations and also documented the finds with great academic curiosity and rigour, inventing - at the time - new ways of preserving the delicate skeleton. Parts of this find are still exhibited today.

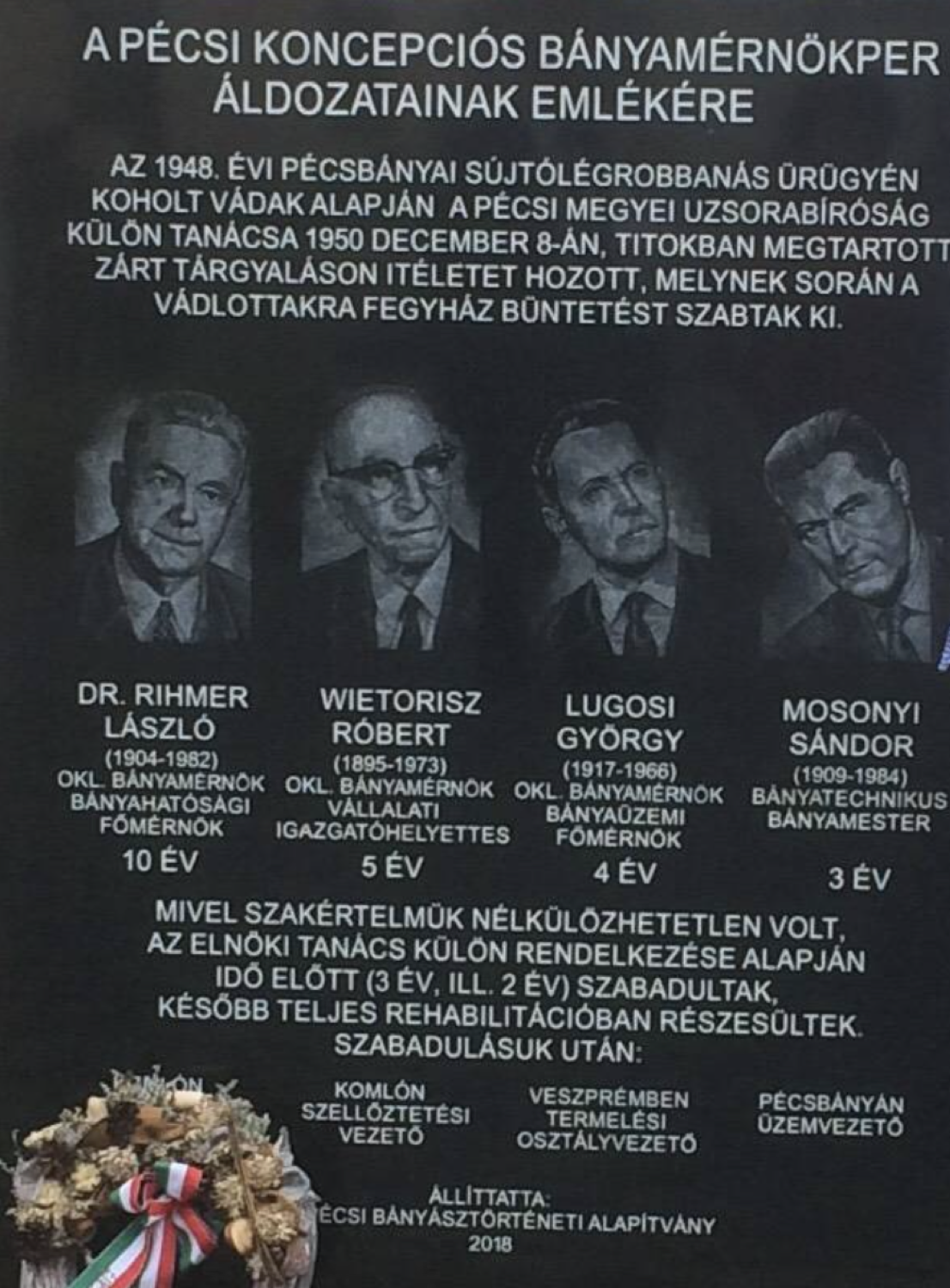

Later, he served in World War II, then returned to Pécs and worked as deputy mining captain. In 1950 they pinned a mining accident on him and as a victim of a typical communist show trial, he was innocently sentenced to 10 years in prison. Fortunately, he was released after three years. He didn’t talk to anyone about the physical and psychological trauma and humiliation experienced in prison for 23 years. Eventually, in 1976 he let these feelings out in the form of a 32-page memoir. While my great-grandfather was in prison, the family had to be supported by his eldest daughter, my grandmother Mária. Because of this, she had to leave school and at age 16 went to work at the Pécs Electrical Installation Company, but was fired when her father’s trial became public. Following this, she got work at the Child Nutrition Company as a secretary. Later she also worked in Budapest alongside her boss, who by then was the company’s managing director.

Gallery

Summary: My paternal grandmother’s line is a family that moved from the Prague area already in the mid-1700s. They were presumably originally German-speaking then they were Hungarianized, and as lawyers, landowners and middle-class intellectuals with strong Catholic roots, contributed to Hungarian society in various roles and capacities for centuries, as they lived in the area of Pécs from 1770 to 1982. My great-grandfather’s imprisonment and persecution, as well as my grandmother’s derailed life and studies, are clearly attributable to the communist regime.

Maternal Grandmother’s Line

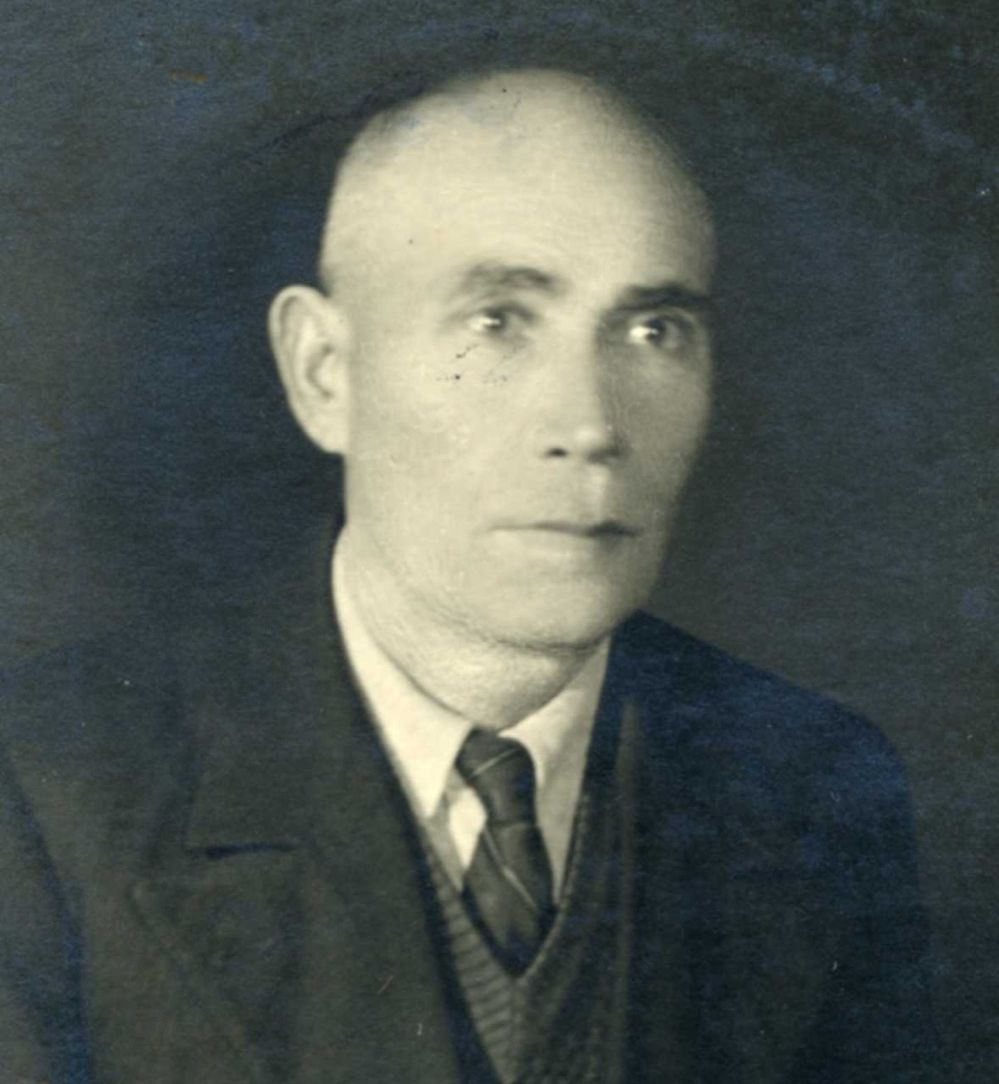

This branch of the family tree can be traced back to the early 19th century. My grandmother’s ancestors were Vojvodina Swabians with German names who spoke German well. My great-grandfather, Dániel, was a professional soldier, a bridge builder, who served on the Italian front in World War I. He was decorated for his service and pensioned from the military with severance pay with which he was able to buy a café and a general store in Szeged. The café was located in Kölcsey street, which is the most central shopping street of Szeged to this day. He threw everyone out of the café after 9 pm because he wasn’t a night owl. This of course didn’t make him very popular with the customers, and eventually he sold the café.

This branch of the family tree can be traced back to the early 19th century. My grandmother’s ancestors were Vojvodina Swabians with German names who spoke German well. My great-grandfather, Dániel, was a professional soldier, a bridge builder, who served on the Italian front in World War I. He was decorated for his service and pensioned from the military with severance pay with which he was able to buy a café and a general store in Szeged. The café was located in Kölcsey street, which is the most central shopping street of Szeged to this day. He threw everyone out of the café after 9 pm because he wasn’t a night owl. This of course didn’t make him very popular with the customers, and eventually he sold the café.

Despite being a decorated soldier who served for his homeland and operated a shop and café in one of the country’s major cities, after World War II he was sentenced to five years in prison and complete confiscation of all his property based on entirely made up political accusations. Like so many of his contemporaries with German heritage, names, and cultural ties, he was falsely accused by the Hungarian government of SS membership. This was outrageously duplicitous as a charge, since the Hungarian government had signed an official agreement with Nazi Germany that allowed ethnic Germans living in Hungary to be recruited into the Waffen-SS by coercion or later by sheer force. My great-grandad was nearly 60 years old, when he was entered into the membership books of Waffen-SS, without his knowledge. Several of his brothers were also “recruited” and were sent to Russian frontlines. One of them, Andreas or Uncle Poldi deserted with a Jewish labour camp prisoner and made his way back to his home in Transylvania, where he hid in his own basement for an entire year.

My great-grandad was 63 when he got released, after serving 2.5 years for these made up charges. Then, to make things even more devastating, based on the principle of collective guilt, the family received a deportation order as part of the expulsion of the ethnic German families.

This is an overlooked and very sad chapter of the post WWII era, where across Eastern Europe half a million ethnic German families were forcibly deported from their homes and sent to Germany and other territories without anything but a suitcase. These families - as my great-grandfather’s - had been living in their home countries for centuries and often arrived there as early as the 17th century, travelling down the Danube.

Upon receiving the deportation order, my great-grandfather strongly considered leaving, since he was badly mistreated and already penniless, but his daughter, my grandmother Liza, appealed to the Ministry of Interior Affairs and as a result they canceled the order. The family was allowed to stay. Not like their 185,000 fellow ethnic Germans, who after often multiple generations or even centuries of Hungarian life became dispossessed and exiled, so that their houses, shops, and lands could be “taken over” by their own neighbors, the “real” Hungarians.

Life’s strange irony is that when we’re in Budapest visiting family, we stay in Budaörs in an apartment building built on the site of a former Swabian house. Its former owners might have been just such Swabians as my great-grandfather. Only they couldn’t stay in their place, poor souls. They were deported under brutal circumstances just as their ancestors had arrived on the Danube centuries earlier: penniless and traveling into nothingness. Interestingly, the stories, culture, and memory of the Swabians deported from (and remaining in) Budaörs and the surrounding area are preserved and maintained by the Jacob Bleyer Heimatmuseum, just one street away from our apartment.

Summary: My maternal grandmother’s line is a German-origin Swabian family who had lived in the southern part of Hungary for several hundred years. Despite fighting for the country in World War I, receiving a medal for his service and living as a respected citizen, my great-grandfather was persecuted, all his belongings were confiscated, and his family was sentenced to forced deportation. Thankfully, this didn’t happen because of my grandmother’s appeal, who was therefore able to meet my grandfather.

Summary: My maternal grandmother’s line is a German-origin Swabian family who had lived in the southern part of Hungary for several hundred years. Despite fighting for the country in World War I, receiving a medal for his service and living as a respected citizen, my great-grandfather was persecuted, all his belongings were confiscated, and his family was sentenced to forced deportation. Thankfully, this didn’t happen because of my grandmother’s appeal, who was therefore able to meet my grandfather.

Gallery

Maternal Grandfather’s Line

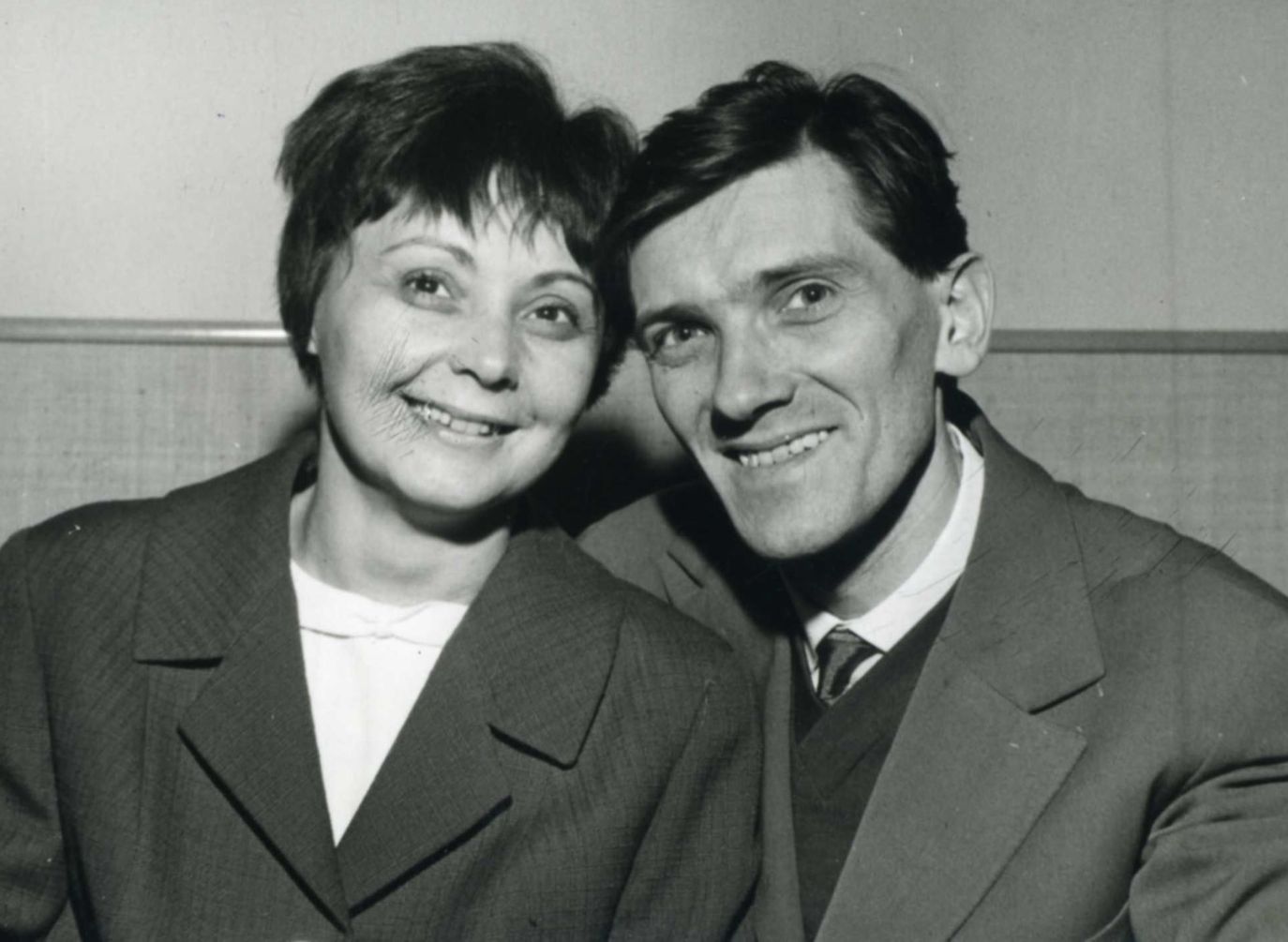

My 3rd, 2nd and 1st great-grandfathers were all Jewish merchants, some of them wine merchants. Within a few generations the family ended up in Budapest via Gyón (Dabas) and Szolnok. My grandfather, Albert (to me Berti) was already born in the capital. He was 14 years old in 1944, during the horrors of the Holocaust. My grandmother wrote down his memories decades after the war, from which we know the following details:

My 3rd, 2nd and 1st great-grandfathers were all Jewish merchants, some of them wine merchants. Within a few generations the family ended up in Budapest via Gyón (Dabas) and Szolnok. My grandfather, Albert (to me Berti) was already born in the capital. He was 14 years old in 1944, during the horrors of the Holocaust. My grandmother wrote down his memories decades after the war, from which we know the following details:

Following the German occupation, my grandad’s family had to wear yellow David stars and leave their József Street apartment in the 8th district. That flat was then promptly taken over by a couple - both devout members of the Arrow Cross Party. This party was essentially the Hungarian Fascist Party and its paramilitary wing - along with its members - played an outsized and bonechillingly bloody role in rounding up the Jews around Hungary. They assisted the Germans with such vehemence and brutality that the Germans themselves were utterly puzzled by this. There are surviving documents that capture the amazement of the SS and German military leaders by the willingness, efficiency and sheer enthusiasm of the Arrow Cross Party members in assisting them in the “Final Solution”.

After they were forcibly removed from their flat, my grandfather’s family moved to the “starred house” - i.e. a house part of the Jewish Ghetto at the corner of Kertész and Dob streets. There they were only allowed to take their personal clothing. This apartment belonged to Dr. Lipót Klug, a university professor, who originally came from Kolozsvár, which is part of Romania today. The apartment was protected by exemption rights thanks to its owner. Klug Lipót’s housekeeper was Berti’s great-aunt, who was also entitled to exemption rights through Dr. Klug. After moving to the starred house, it was no longer possible to work or pursue any studies. Following the takeover of the Arrow Cross Party on October 16, 1944, their members and SS soldiers herded all four of them (my grandfather, his two sisters, and his mother) down to the building’s basement and confiscated all their belongings - with body searches. On the same day, my great-grandfather, Dezső, managed to escape from a labor camp in the southern region of Hungary and found his family in the basement.

That same evening around 10 o’clock, the special units of the Arrow Cross Party and SS soldiers drove them out of the house again. They lined them up in rows of five on Dob Street and with another body search took away the remaining items still with them, saying: “You won’t need these anymore.” Word spread that they were taking them to the Danube bank for execution. A German Tiger tank stood behind the rows of terrified people. Together with similarly rounded-up people from surrounding streets, there were several thousand of them. Meanwhile someone appeared - later presumed to be Raoul Wallenberg. He was a Swedish diplomat who managed to save thousands of Jewish families by issuing protective passports to them. Later, he was captured by the Soviets and presumably killed. He was only 35 at the time. Wallenberg began negotiating with the special units taking my grandfather’s family and thousands of Jews for execution, and as a consequence they were herded not to the Danube bank but to the Kazinczy Street synagogue. Here they languished for four days without any kind of food. After four days, Hungarian police opened the synagogue and asked everyone to very quietly return to their previous starred house.

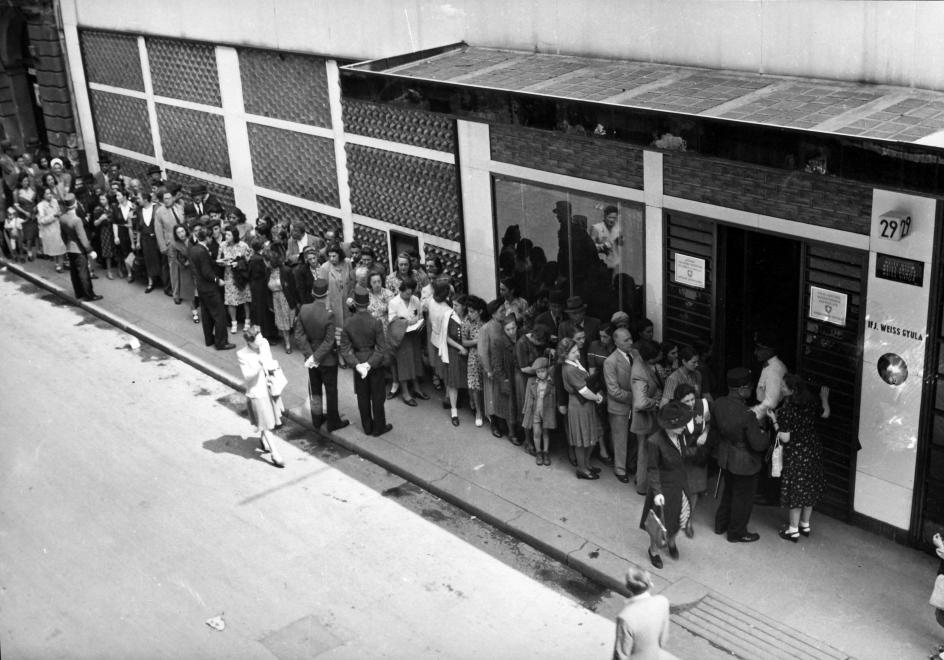

The story continues from here with further incredible turns. Despite the fact that my grandfather’s sisters and father were already taken to do forced labor in the Óbuda brick factory, my grandad was able to obtain protective passports for all of them, by patiently standing in line in front of the “Glass House” on Vadász Street. This building was where the Swiss Legation’s Foreign Interests & Immigration Department operated at the time. The operation in the “Glass House” was nothing other than an incredibly large-scale Jewish rescue operation organized by Carl Lutz, the contemporary Swiss consul. Within this programme more than 50,000 illegally issued protective passes were given out, which entitled the holder to emigration to Palestine. Furthermore, as part of the programme, the pass holders could shelter in relative safety in one of Switzerland’s 76 protected houses. After obtaining the passes, and escaping from the brick factory, my grandad’s family moved to one of these, at 16 Pozsonyi Road. The Swiss protective pass program - comparable to Wallenberg’s efforts - verifiably saved several thousand families, even though the Arrow Cross Party regularly raided these safe houses and dragged people away for execution.

This happened to my grandfather’s sisters and mother too, whom the fascists took to the Danube bank to execute. My grandad was deemed too young and my great-grandfather too old to be taken on this occasion. With incredible luck, a Soviet Rata fighter plane was flying low over Szent István Park, which frightened the Arrow Cross guards escorting the abducted and they scattered. Taking advantage of this situation, the group also broke up and the girls and my great-grandmother fled back to the protected house. It was already mid-January, one of the most intense phases of the siege of Budapest, when the Arrow Cross raided again and moved them to the Dob Street ghetto. On January 18th they noticed that Soviet soldiers had appeared on the street. For the first time in years, they could breathe freely then. Miraculously, the entire family had survived.

My great-grandfather’s sister, Margit and her family weren’t so lucky. They were deported and died in Auschwitz. So did nearly 600,000 Jewish Hungarian citizens, whom the Hungarian state apparatus sent to death with unprecedented efficiency and cruelty. Less than half of the capital’s Jewish population survived the Holocaust, but this was still much better than what happened to rural Jewry. After the World War I’s Trianon treaty, 704 Jewish communities existed in 1939, but only 263 in 1946 after World War II. In the following years their numbers gradually decreased due to emigration, state pressure, and the breakdown of traditional lifestyle. In Transcarpathia, about 400 communities operated before the war, twenty in 1946, only four by 1950.

Gallery

Summary: My maternal grandfather’s line is a Jewish merchant family, which was only partially successfully exterminated, thanks to the Swiss embassy’s rescue operation and the Swedish Wallenberg. Understandably, after the Holocaust, my great-grandad changed the family’s name from Schwartz to a more Hungarian sounding one.

Who Can Live Here?

On the paternal side, we therefore see families settled from Slovakia and Czech Republic who had lived, even prospered in Hungary for generations, living respectable bourgeois lives. They were independently subjected to serious trauma during the communist era.

In contrast, on the maternal side we find long-settled Swabians, with a decorated war veteran who was later still condemned to prison and deportation, and a half-exterminated Jewish merchant family.

The question therefore arises in one’s mind: who exactly can live undisturbed in this country? From the above it seems that one can live here for hundreds of years and can be:

- Catholic, Protestant, or Jewish,

- an engineer, a lawyer, a soldier, or a merchant,

but Hungary will still hold little “surprises” for them nonetheless.

I’ve been thinking for weeks about the commonality in these fates. I felt that something connects these stories, but I couldn’t precisely articulate what. Until one morning lying in bed it occurred to me: I can’t find a word for it because there isn’t one. So I created one: “reverse-treason,” that is, treason with full role reversal.

My ancestors didn’t betray their homeland,

instead their homeland betrayed them.

Without exception. All of them. After multiple generations of active and enthusiastic contribution to Hungary, regardless of where they lived, what they believed in, and what they did for a living, this country once decided to sideline them or even exterminate them completely.

When I finally saw this clearly and dared to say it out loud, then almost twenty years of repressed tension and soul-searching ended within me. In a cathartic way, but still without any anger or emotion, and with a big sigh, I finally arrived at the closure of my relationship with Hungary. It was gone and done. Forever.

Epilogue

The reader might justifiably wonder whether the same fate would have awaited my ancestors in Poland, Czechoslovakia, or Romania too. If so, Hungary is not unique and my ancestors’ embarrassingly unanimous stories can be explained purely by the blood-soaked 20th century and Hungary’s geographical location. Although I can’t rule it out, I doubt it would be so, and what’s more important, it wouldn’t change the story’s final conclusion for me in either direction.

However, there is something that could have changed my conclusion - beyond avoiding the reprehensible politics of Orban in the last 15 years. And that would have been if I didn’t feel that this state, this country is still very much capable of betraying its citizens yet again, as it did with my ancestors. But not only do I not feel this, I fear we’re closer to reverse-treason today than we were 30 years ago. I don’t know why this is so, but I suspect the following ingrained patterns strongly contribute.

With few deeply deserving exceptions, most nations love to deflect historical responsibility and avoid confronting their questionable past deeds. When they do reckon with it, they often do so belatedly, offering inadequate apologies while relativizing their actions. This is true for countries ranging from Great Britain to France to Belgium. But Hungarian historical memory unfortunately goes even beyond this—not only failing to face numerous shameful historical facts, but actually casting the country’s role in a victim narrative, which creates completely perverse situations.

This happens when Hungary minimizes, relativizes, and even declares essentially irrelevant its role in the systematic, decades-long marginalization of Hungarian Jewry and the destruction of 70% of them, deflecting blame onto the Nazi occupation. This extremely cynical and self-reflection-incapable historical memory emerges in folk legends like the claim that Horthy was a savior of Jews - which is a lie - or the unqualifiable heap of kitsch meant to commemorate the victims of German occupation, which grotesquely depicts Hungary as an angel being kidnapped by an evil German eagle. Against these romanticized lies, reality shows a much more bone-chilling and sobering picture of the Hungarian government’s and Hungarian population’s actual role.

Hungarian historical memory does the same thing when processing the violent deportation of ethnic Germans. Then it’s customary to play the well-worn victim narrative trump card of the Potsdam Conference, claiming that the violent deportation of 185,000 ethnic German minority happened purely at the request of the victorious powers. This, however, is simply not true.

And what can we say about confronting the communist past in a country that still hasn’t succeeded in making communist era files public to this day, thus completely preventing the nation from coming to terms with the trauma and wounds inflicted by communist era? What can we say about a country, where the ruling party of 16 years - though fiercely nationalist and anti-communist while simultaneously pro-Russian - still contains several Communist Party members, and agents of the dreaded Communist State Protection Authority in high government positions. And finally, what should we do with today’s Hungarian government, presenting itself as a victim, whining about its “grievances” and advancing Russian propaganda, while its neighbour, Ukraine - where Hungarians also live in significant numbers - has been bombed, butchered and terrorized by Putin’s regime for three years?

These and numerous other historical examples show that Hungary’s capacity for historical self-reflection has been in deficit for several hundred years. Instead, a victim narrative - incompatible with historical facts - is often the dominant reflex that determines Hungary’s historical self-image.

It’s a cliché repeated countless times that if historical crimes aren’t confronted by a critical mass within a country or ethnic group, then that society cannot learn anything from what happened. This obviously creates fertile ground for future tragedies.

I can only hope that after another generation passes, these reflexes will improve in Hungary, but I wouldn’t bet my life on it. The problem is that while being 1000 years old looks good on a tourism brochure, it’s also a double-edged sword. Namely, 1000-year-old things rarely change, and especially rarely renew themselves.**

Comments