The 1 minute version

I was part of the EF12 London cohort in 2019, where I met my co-founder. Together, we pursued an idea that I had for a while:

A privacy-preserving medical-data marketplace and AI platform built around federated deep learning.

The purpose of the platform would have been to allow data scientists to train deep learning models on highly sensitive healthcare data without that data ever leaving the hospitals. At the same time, thanks to a novel data monetization strategy and marketplace component, hospitals would have been empowered to make money from the data they are generating.

We received pre-seed funding, valued at $1M. Then the race for demo day began with frantic product building and non-stop business development. Unfortunately, my co-founder fell out of love with the idea after enduring months of business development hardship. Then we failed to pivot to something we both liked, so we split up and I went on my own way.

The whole ordeal was an amazing mixture of fun, challenging learning opportunities and uninhibited misery (but mostly fun). Make sure to check out the demo of the MVP I built.

If you are curious about the details of the story then read on. If you’re in a rush, feel free to skip ahead to the list of things I learned from the experience.

How to find a co-founder?

Back in early 2019, I left my job at IQVIA to join the London cohort of Entrepreneur First. EF is an amazing incubator / accelerator programme that has given the world the likes of Magic Pony and hundreds of other exciting companies.

Entrepreneur what?

The main thing that sets EF apart from the dozens of similar programmes is that they focus on the earliest possible stage of companies: sole founders. They take in a hundred talented and ambitious individuals in each cohort (actually almost 200 when you count the other European EF sites: Berlin and Paris).

Then the good people of EF will

make everyone go through a weird, speed-dating meets Love Island type of co-founder finding process.

In this phase, for weeks on end, you are simultaneously reading the CVs of super interesting cohort members and having ludicrously blue-sky chats with them, about potentially world changing companies the two of you could build. By the end of this process, you should end up with a co-founder.

EF also gives you a stipend, a place to work and a ton of high quality material on the basics of entrepreneurship and startup building. But I think the real USP of EF, is the access to this pool of pre-screened, highly talented and motivated people, who all left their (sometimes lucrative) day jobs to become members of the cohort and build companies.

From beers to business

As a naturally sceptical person, I wasn’t sure what to think about this process. I did what was expected of me (reading CVs, talking to people, coming up with outlandish ideas) but I didn’t really click with anyone.

Finally however, after many beers and chats, I found my co-founder, with whom we just had enough in common (interest in healthcare and machine learning) to make our discussions fruitful, but with whom our skills were complimentary enough that we could take advantage of having two people on the team.

This latter point is in fact quite crucial: too often, we are naturally attracted to people with similar interests, skills and thinking to our own. This is great for friendships, but can be devastating in a startup where

you want the co-founders to cover each other’s blind spots.

Both my co-founder and I are “techies” in broad terms. But it was quite clear from the beginning that I am more of a CTO type who loves to build, whereas he liked the process of selling and pitching, which is quite important because that’s pretty much all you do as an early stage startup CEO.

Fortunately (as this is quite rare AFAIK), we both had a good share of the skills of the other’s role too. This really helped with both the technical and business discussions between the two of us.

Do you have a $1B idea?

Something we all learned fairly quickly in EF was the economics of venture capital. It’s really quite simple and goes something like this:

Venture capitalism 101

- There’s a huge amount of excess money slushing around in the global financial system.

- Most investors stratify their investment portfolios according to some risk profile. This usually means that they are happy to put 1-2% of their capital in high-risk ventures. Funding highly risky tech startups is one of these high-risk venture types. Another would be to buy crypto for instance.

- VC firms utilise this and go out every $latex x$ years to raise a round, i.e. pool together capital from wealthy individuals and investment funds.

- Whatever they raise is the fund that can be allocated by the partners of the VC firm, as they see fit.

- Most VCs work on a 2/20 rule: they will take 2% management fee each year, plus 20% of any profit they make.

- It’s worth noting here, that 2% of a billion-dollar fund is still a few million for each partner each year, even if none of their funded companies exit or do particularly well. Yeah, being a VC is quite lucrative.

- VCs promise extraordinary returns to the investors. Certainly well above anything that’s attainable with reasonable risk profile on the market. How can they deliver?

- To achieve this they can either fund companies where they expect that most of them will grow 100%.

- Or fund companies where none of them will grow a 100%, because most will grow 0%, and potentially one or two will grow 1,000% or 10,000%.

Companies from the first group are called successful medium sized business. The latter ones are called unicorns: startups in hyper-growth mode, overtaking and disrupting a whole industry like AirBnB or Uber did for example.

Not all ideas are created equal

Even though probably both investment models could be equally successful, VCs want to invest in high impact firms that will change the world. Think Google, Facebook, Twitter.

I leave it to your judgement whether this is a healthy and sustainable business model. I will certainly write more about this in the future, but I will say this: VCs serve a super important function in the global innovation market and without them, the world would be different in countless ways.

The corollary of all the above is that if you go down the VC backed startup building path, you need an idea that can become a 1 billion-dollar company. Yes, that’s a billion with a B.

Start me up!

We spent weeks ideating with my co-founder, but after dozens of discussions we came back to the idea I arrived to EF with. It was the only one that seemed simultaneously ambitious and high impact enough that a VC might take a liking to it, while also having the potential to grow into a multi billion-dollar company. Also, neither of us hated it, which is quite important, I heard.

The idea

I had this idea for a company for months before applying to EF:

The world’s first, privacy-centered medical-data marketplace and machine learning platform, powered by federated deep learning.

I couldn’t wait to tell all the people at the cohort about it, so I did. And they all made the exact same face you just did when you read the sentence above.

The problem with deep tech ideas (besides not fitting on a napkin) is that for the most of us not well-versed in the particular field, they are often indistinguishable from vaporware and snake-oil.

You really have to know a lot about healthcare informatics, medical machine learning, federated deep learning and also the financial incentive structure of the US healthcare industry to properly evaluate that one sentence above.

If you do that, it will not only make a lot of sense but you’ll find that it’s offering one of the very few viable long-term solutions to the impossible trade-off healthcare faces in the 21st century:

The patients’ natural right to data privacy is in direct conflict with data pooling and with how much we can learn from this data with current AI algorithms.

This is bad news, because without the deployment and proliferation of AI, healthcare is doomed. Another indication that the above idea might not be the worst ever is that Google Ventures already backed an amazing team to do exactly this. Yeah, finding that out wasn’t fun…

The idea explained

Probably it’s easiest to explain the idea for our startup by enumerating some of the relevant problems that plague healthcare currently:

- Hospitals and outpatient clinics generate vast amounts of incredibly rich and detailed data about patients. We’ll call these institutions providers.

- This generated patient data is extremely sensitive, and people are rightly concerned about who gets to use or analyse it.

- Pharmaceutical companies, biotech and medtech AI startups are all hungry for this data and could develop amazing new drugs, therapies, diagnostic tools, algorithms by leveraging it. We’ll call these companies vendors.

- Providers are often cash-stripped and as a consequence struggling to provide the highest quality of care for their patients.

- Vendors have ample resources (money) and a clear need to access this data. Furthermore, by providing this data to them securely, the world could undoubtedly become a better and healthier place through their innovation.

- Even if vendors had access to this data, deploying AI models at scale, in a live hospital setting is still one of the biggest unsolved challenges of digital healthcare.

Once you write down these six simple facts about today’s healthcare systems, it really doesn’t take long for the light bulb to start flashing.

We need to build a marketplace where providers can sell access to their data without compromising patient privacy and where vendors can get access to this data to learn from it and train models on it. Furthermore, once vendors have a model trained, they need to be able to easily deploy it to network of hospitals, where those models could start to generate useful (and potentially life-saving) predictions.

But how could anyone use sensitive data without actually having a look at it, thereby immediately compromising patient privacy?

The answer is quite remarkably simple, and it’s been powering all sorts of technologies (like predictive texting on your phone) for years. It’s called federated learning and it’s first real-world, large scale application came from Google (as far as I know) following this paper. Then, many - more - followed and amazing open source libraries were released like PySyft by OpenMined, or FATE by WeBank.

Federated learning’s simplest explanation can be boiled down to a single sentence:

Instead of moving the data to the model, let’s move the model to data.

Suffice to say that this idea has found applications in several security and privacy conscious industries, but its impact on healthcare will truly be transformational. Have a look at these two recently published Nature articles to see what federated learning holds for the future of multi-institutional medical studies and digital health applications.

If you’re curious about the technical details and implementation of our idea, make sure to check out this page about the MVP I built, or watch my demo of it below.

To recap

- We wanted to build a platform to enable researchers and data scientists of pharma and biotech companies to access highly granular and information rich patient data from US hospitals to train models on it,

- without the data ever leaving the four walls of those hospitals and without the researchers ever being able to actually look at the data.

- We wanted to leverage federated deep learning and a federated data query engine to achieve this.

- The best part? The hospitals would have made money out of the mountains of data they are sitting on, without ever compromising patient privacy, while simultaneously enabling vendors to innovate, research and develop therapies.

- Furthermore the learned algorithms could have been deployed back to the federated hospital network and put to good use.

- We wanted to charge vendors according to the well-known SaaS business model and share a sizeable fraction of our revenue with the hospitals so they become financially incentivised to partner with us.

- How? Every time a hospital’s data would have been used to train a model, they would have got compensated based on the number of patients and data granularity they provided for the study.

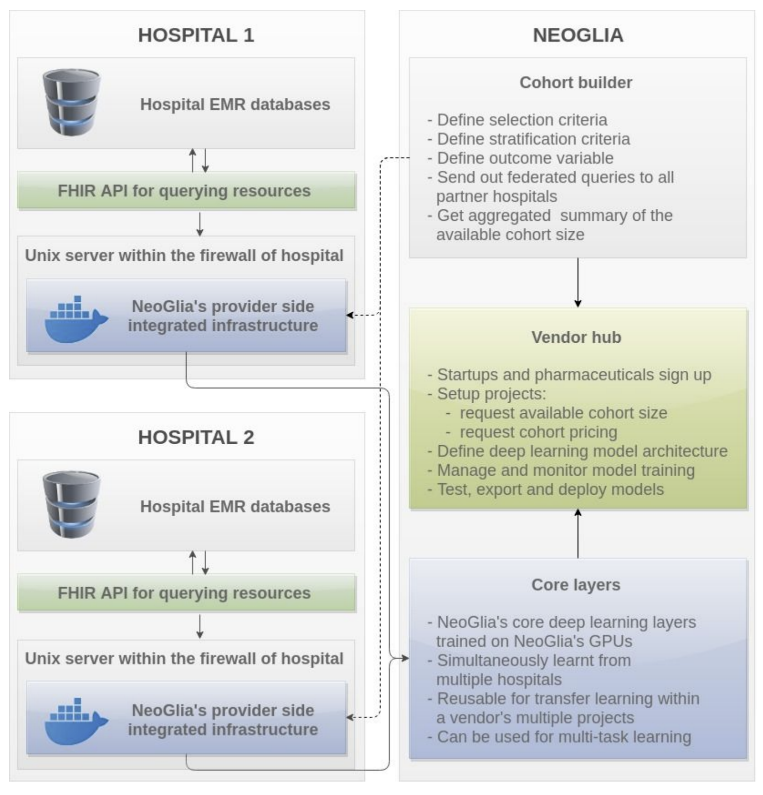

Here’s a flowchart of the smallest possible incarnation of our platform with just two hospitals connected to the federated data network.

The rollercoaster of founder life

The EF programme is structured according to a fairly well thought out schedule that gives a nice framework for working on your idea.

- In the first few weeks you should get data about the market’s reaction to your idea. This means you’re constantly on the phone (sometimes for 6-8 hours straight), talking to people, who are often not that interested, but you begged your way in or forced them some other way.

- You’re doing all of this to basically “Mom test” your idea.

- This is a neat little trick to get around the problem of people being too nice. Yes, that’s actually a problem, as they’ll outright lie in your face and say that they like your idea and would even pay for it. Only then to completely disappear after the call.

- The reason for this is quite simple: no one likes to be the a-hole who breaks the soul of budding entrepreneurs. Contrary to popular belief, people on average are fairly nice that way, so they’ll naturally try to say something good about your idea, even if it’s objectively terrible and they knew from the second minute, they’ll never ever use it.

- In this early phase, it’s not a big deal if people are hanging up on you. You should just have as many calls as possible, be resilient and accept that no one cares about your idea besides you. Keep your head down, collect data and try to find out if there’s anyone out there even remotely interested in buying what you have to offer.

- In the next phase of your VC fuelled company building, you are trying to produce some form of “traction” to prove to your future investors (the EF Investment Committee (IC) in our case), that in fact, your idea is a viable business.

- Traction can be many things, depending on the complexity of your product. Here are a few types of traction in decreasing order of impressiveness:

- Signed up users / companies with their card details already taken, ready for doing business with you.

- Signed contract with another business for a (hopefully) paid trial. Contract for an unpaid trial is the next best thing here.

- Letter of intent from another company or institution. This is usually a document with purposefully vague and legally non-binding language in which your future client (you wish) says that they don’t think your idea is totally crazy and (if the stars align and the director wakes up in the right good mood) they might even consider using it one day. Maybe…

- Then you take all this evidence that you’ve gathered through hundreds of interviews and thousands of emails and present it to the EF Investment Committee. If they like your idea, you get £80k for a 10% stake in your company. You get to work on it more till you reach the maturity to pitch your company at demo day to dozens and dozens of great VCs with the intention of raising a seed round (~£1-2M) with one of them.

- If you get seed funded (usually 4-6 months after demo day) then hurray, your VC fuelled company building journey can finally begin. Unfortunately, the odds are still heavily stacked against you:

- There’s only about a 20% chance you’ll make it to the next funding round. Quite annoyingly, you’ll need several of those in the coming years to keep your unicorn alive - they are hungry beasts.

- There’s a 97% chance that you’ll fail to exit, i.e. fail to turn your years and years of gruelling work into hard earned millions.

Hm… That was depressing to learn, but don’t worry, it’ll get worse.

The up

As anyone who’s ever tried will tell you, building a company is like being on a rollercoaster ride. Sometimes you have days that feel like none of the days in your previous office jobs. You feel amazing, fulfilled and working on something truly meaningful (at least to you).

Even better, sometimes things just work out. Like when we started to ask huge and well-known US research hospitals if they would partner with us (two random unfunded guys from London) to build the world’s first federated machine learning platform for healthcare and they just said “yeah sure”.

Or when the second and third meetings started to occur with these teams, and the term “letter of intent” started to fly around a lot. We felt invincible. Even if it took more than a hundred Zoom calls and thousands of emails sent out, we thought we are clearly making progress with business development here.

The top

Then the rollercoaster continued and took us to this amazing top. Armed with our letters of intent and signed project proposals with these hospitals, EF’s IC said they’d invest in us and just like that, we got the pre-seed funding.

Roughly 30% of the initial EF cohort make it this far so we felt great. Even though we knew the work is just about to get a whole lot more challenging and crazy, there’s a moment when you have your first little success and you start quietly wondering to yourself:

Maybe we’ll be among the 1% of startups that actually make it… I know it’s unlikely, but maybe this will all just work out fine!

I was also super excited that I get to finally build again after months of not coding. Don’t get me wrong, conducting BD calls, writing marketing materials, technical documents, grants, drafting SOWs and LOIs was extremely educational too and they are necessary and unavoidable parts of every company formation. Nonetheless, I was itching to actually get back to the thing I love doing and I’m reasonably good at.

The down

After the pre-seed investment, I was 100% on building and my co-founder was 100% on business development. We only had 2.5 months till demo day to:

- Build an MVP of the highly complex product we envisioned.

- Get extremely conservative and risk averse pharma companies and hospitals to sign up with our marketplace.

Our plan seemed straightforward. I am going to take care of the first one and my co-founder is doing the second. Even though we knew the second is probably dependent on the first being ready, we agreed to work as hard as we can and try to have our first customers by demo day in late September 2019.

However, the cracks started to show quite early on… The business development process went from painfully hard (pre-IC) to near impossibly hard (post-IC). Many people told us that letters of intent are worth the same as toilet paper, and we should try to convert those into signed contracts for paid or unpaid trials ASAP, so that’s what we tried to do.

Despite my co-founder’s heroic efforts however, after months of negotiations, meetings, project proposals and more meetings with US hospitals, every single lead of ours simply dried up. Emails went unanswered. Crucial final meetings with the key stakeholders did not happen.

When the discussions turned real, and when hospitals realised that for this fancy-sounding research project they’d need to actually provision resources for us so we can integrate our software into their IT systems, they went cold turkey on us.

The small up before..

We realised that we made our own lives impossible by trying to aggressively innovate on two fronts at once:

- We wanted to build a federated ML platform for deep learning models in a notoriously conservative industry, leveraging highly sensitive data with tons of regulations around it.

- We wanted to create a marketplace, therefore we had to find not just one customer type but two: providers and vendors too.

Even just one of these goals would have been insanely hard for a two-person team to pull off in 6 months, but doing them together was clearly way too much. So we pivoted and said:

Let’s sell our federated ML platform to pharma companies. Let them use it with their existing hospital relationships however they see fit.

This wasn’t the worst idea to be honest. Pharma companies already have longstanding relationships with hospitals and outpatient clinics, as these connections are essential for recruiting patients for new clinical trials.

Healthcare - as we found out to our own detriment - is built on trust and slowly evolving long-term partnerships. There’s very little place for disruptive technologies, especially pushed by small companies. Due to the heavily regulated and risk averse nature of healthcare, you can have the best tech product and it’ll still be extremely hard to sell (this was confirmed to us by numerous companies on the market).

So we thought, let’s sell the technology to the innovation leads and heads of data science of large pharma companies. Then they will take care of getting the tech to the data, i.e. inside the hospitals.

The crash

This hasn’t really changed the MVP I had to build, only the way we’d demo it to users potentially, so I proceeded further with full steam.

My co-founder in the meanwhile was trying to line up as many demo opportunities as he could, so we would have a good chance of converting at least one or two of those into an unpaid trial by demo day. Then we’d have our hard-won “traction” in our hands for our discussions with VCs.

I finished the MVP and we started to demo it to large pharma companies. Quite miraculously, none of them thought it was terrible. In fact, some of them even murmured something positive about it during the call.

But crucially, none of them jumped out of their chair singing Hail Mary, thanking us for finally solving their long standing hair-on-fire problem. Instead, they all said, they’ll get back to us after they had some internal discussions.

Although sales cycles in healthcare are notoriously long, and selling to pharma as a tiny startup is near impossible, we knew we missed the mark. We could simply feel after these calls that we aren’t solving any of these teams’ top 3 problems. What we offered was definitely in the top 10 or 15, but not even close to top 3.

And then, to make things worse (or better?)

through a series of honest chats with my co-founder, I found out that his heart isn’t really in federated learning anymore.

Turns out, it’s a pretty big problem when the CEO of a company is not emotionally invested in and hyped up about the very thing the company is selling. It’s especially bad if this happens literally weeks before he’s supposed to stand in front of a hundred VCs and convince them that our business is the one that’s going to change the world and which is worth their £1M investment.

Operation Salvage

I totally empathised with the frustration of my co-founder after he struggled for months to sell without much to show for it… However it felt rather bad to give up on the idea at the very last minute.

Granted, our traction was practically non-existent at that point, but I suspected from the beginning that selling this product will be incredible hard and might potentially take years. We also knew for a fact that selling our product isn’t impossible, as we have found companies that managed to get into US hospitals and others that worked successfully on something similar to our idea (although both with incredible funding behind their backs). So personally I wasn’t disappointed, and I wasn’t that surprised with our lack of progress. But clearly my co-founder was and it was him who had to muster the energy day after day to try and sell this thing.

It was pretty clear to me that just like you cannot make someone love another human being, you cannot make someone feel passion for something for which they simply don’t. So reluctantly, I agreed to move on and use the rest of our pre-seed funding to build something else for the next demo day (which was scheduled for 6 months later).

We told our plans to EF (who were really nice and supportive about it), then proceeded to conduct one of the most painful 4 weeks of my life. We brainstormed in the Google Startup Campus, the British Library and countless pubs and cafes of London for days on end. We were desperately trying to come up with an idea which we both felt good about, meaning we would be willing to dedicate a couple years of our lives to it.

Whiteboard sessions came and went, beers and many more coffees were had. We tried for hours each day, but one of the two following scenarios kept happening:

- Either founder A hated the idea founder B just pitched or,

- we both quickly realised that founder B’s idea was genuinely terrible, so we just laughed (or cried).

The end

After weeks of this, I proposed to leave the company and sell my shares to my co-founder. Again, EF was incredibly nice about this and signed all the necessary contract modifications that allowed me a clean exit. Then, on a rainy October day, six months after joining EF,

my co-founder and I said goodbye in a typical London pub and that was the end of my first startup.

As I walked towards the tube, lots of thoughts and feelings were rushing through my head… None of them particularly positive or pleasant, but I knew I made the right decision.

Takeaways

I probably learned more about myself and the world in those six months than in the preceding 2.5 years in my typical 9 to 5 corporate data-science job. I couldn’t possibly summarise all of it here and some (or most) of it might be completely trivial to some readers. So here’s a list of my top learnings.

What did I learn?

- Product market fit is (almost) everything. It’s a simple sounding but pretty complex idea. Here’s a good intro to it, and here’s the best step by step guide I’ve found so far about how to achieve it.

- Ideas are cheap. Execution is all that matters. It’s been repeated ad-nauseam in startup circles but I think it’s mostly true so worth noting. Although, some successful people challenge this and advocate the exact opposite. The truth (as usual) is probably somewhere in the middle, but definitely closer to the “ideas are cheap” side.

- Related tip: never be afraid to talk about your idea. It’s the only way to find funding and co-founders (and most likely you’ll need at least one of those).

- The tale of two ideas: imagine you have two ideas, X and Y. Let’s say, idea X solves a problem, which for a 100 people is so serious, they’d sell their kidneys (both in fact) to get it fixed. Idea Y solves a problem for a 10,000 people and they’d be willing to pay (they say) $20 for it. Which one you should pursue? Before EF, I would have chosen idea Y in a heartbeat. Today, I’d kill to have an idea that is like X. Always choose idea X.

- Finding a great co-founder is exceptionally hard, although I definitely lucked out with mine on many fronts. In general, and contrary to popular startup wisdom, I’d prioritize the following qualities above charisma, genius-level IQ, qualifications or anything else:

- integrity & honesty

- intellectual rigour & logical consistency

- good (but not crazy) work ethic & resilience & patience

- sense of humour & being able to laugh at oneself

- Creating a great team of first 10 employees is even harder than finding a co-founder (from what I heard) and it’s probably the most important thing any founder will do after securing funding, as it will most likely determine the culture of the entire company for many years to come.

- Sales, marketing and UX are super important. Probably more so than your code (especially at the beginning).

- Related tip: don’t be the dumb tech guy that builds it, expecting the users to just show up and start using and loving it.

- Mom test everything.

- Being able to evaluate business ideas critically is a fundamental skill for founders. The good news, that it can be learned. Also, a good checklist helps.

- Spending time on finding out what is it that you’d work on even if you didn’t get paid for it, is an amazingly useful way of focusing your life and career.

- Some healthcare related takeaways I wish I knew before starting:

- Healthcare is conservative, built on trust and slowly evolving but longstanding relationships and partnerships.

- As a not surprising consequence of this, the average age of founders of unicorn healthcare startups is significantly higher than of tech unicorns.

- Also, healthcare seems to be the only industry where having a PhD and many years of relevant experience is a prerequisite of being successful. In most other industries a BSc and/or an MBA seems to be enough.

- If you are planning to build and sell any tech related product in healthcare, be prepared for extremely long sales cycles, business partners who proceed with extreme caution and who care a lot about the optics of your company.

- Therefore, all in all, healthcare is not best suited for tiny startups, created by starry eyed 20-30 something founders with tiny professional networks and little work experience in the field.

What do I miss?

Being a founder of your own deep tech company feels amazing on most days. Here are some of the things I miss:

- The autonomy, responsibility and fast pace is infectious and invigorating. Especially coming from a traditional healthcare behemoth like IQVIA.

- Living in a “Come on, we can do this!” mindset and being surrounded by people who think that way.

- Being surrounded by motivated, ambitious, highly educated and driven people who chose to veer off the traditional corporate track is amazing. Again, in my opinion this is definitely the USP of EF.

- Being able to determine the work schedule and culture of your team.

- Being able to just spend a whole day on learning about something, because that’s what the business calls for.

- Talking to other founders and potential customers teaches you that the world is so much more complex, interesting and nuanced than it seems as an employee in a small vertical of a single industry. There are hundreds of industries, all with their own inefficiencies, suboptimal solutions, knowledge gaps, tech hurdles. Learning about these is fascinating and broadens you as a person and as a professional.

Will I do it again?

Absolutely! Although I might take a different funding route.

But that’s a topic for another post…

Comments